You may be surprised to learn that the growing Democratic or New Economy that puts people and the planet before profit is not actually new. Its principles of a thriving local economy, economic opportunities that benefit all, and ecological sustainability can be found in the Native American worldview. Native American history prior to colonization shows a culture based on an ethos of community and kinship with the land. There was communal ownership of land, a regenerative agricultural system, and care for the common good.

On my road trip being planned for Spring of 2020 I will be visiting Porcupine, South Dakota where a Native American sustainable community and social enterprises are being brought to life based on people, planet and prosperity. I learned about it in The Making of a Democratic Economy co-authored by Marjorie Kelly and Ted Howard of the Democracy Collaborative, which is filled with concrete examples of the New Economy being put into practice. I am especially excited about learning more about Thunder Valley, which is described by a Native American participant as simply “a new economy that is really a return to what our ancestors always knew.”

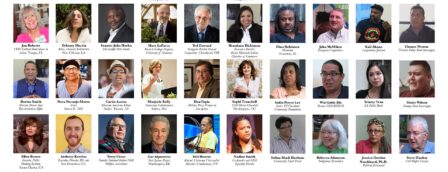

My interest in Native American culture was sparked on my last road trip to interview change-makers when I videotaped five Native Americans, who were immersed in work to improve the lives of their people and the well-being of Mother Earth. I am embarrassed to admit that it wasn’t until then that I was able to have a minimal understanding of the damage done by the colonization of Native Americans and Native Alaskans. I met and learned from these change-makers in the arts, human rights and business communities.

I remember interviewing soft-spoken Terry Cross of the Seneca Nation and Founder of National Indian Child Welfare Association (NICWA) on my stop in Portland, OR. He recounted the unfathomable horror of the Boarding Home Movement sponsored by the federal government and Catholic religion that separated children from their families in order to eradicate Native American culture. He spent months traveling to tribes to document traditions of lullabies and child rearing that had been practically extinguished by the dominant culture. Now, those traditions are the basis of the positive parenting education offered by NICWA to help overcome the generational damage to family life. Terry is proud of the efforts of his organization in Alaska that has intervened and significantly reduced the placement of Native Alaskan children into foster homes.

In Santa Fe, I was moved by Santa Clara Pueblo Artist Nora Naranjo-Morse’s love for our planet. She lamented how “my own people”, who have always lived lightly on this earth are slowly losing touch with their traditional way of being. Her huge clay teepee installation in front of the Smithsonian’s American Indian Museum called “Always Becoming” exemplifies the natural cycle of life—born out of the earth and return to the earth. Nora left a lasting impression on me with her profound compassion for our home and her deep dedication to making a difference.

“Denver has the only American Indian Commission codified by law”. Those were the words proudly spoken by Darius Smith of Navajo heritage and Director of Denver’s Human Rights Office, when I called to ask for a video interview. Enthused is a mild description of Darius’ love for his people and his commitment to the Commission’s focus on eradicating the stereotyping of Native Americans as losers in one way or the other. I learned so much from him about the myths of people living off of Casino profits and government handouts and the toll on Native Americans from generations of domination. I even had my eyes opened about Florida State University’s usurpation of Seminole culture by its football team known as, you guessed it, the Seminoles. Darius did tell me, though, that a dialogue between the tribe and the university did result in some changes in the way the Seminole mascots dress and behave. Like many civil rights leaders, he notes the small victories that keep him going.

I will interview more Native Americans on my road trip in the Spring 2020. For instance, I am appalled that 4 in 5 American Indian and Alaska Native women have experienced violence. Alaska Native women continue to suffer the highest rate of forcible sexual assault and have reported rates of domestic violence up to 10 times higher than in the rest of the United States. Non-native spouses cannot be legally charged or convicted by tribal law. I intend to interview people involved in the Indian Resource Center’s Safe Women, Strong Nations project to end violence against Native women and girls. They work to restore tribal criminal authority and to preserve tribal civil authority as well as help Indian nations increase their capacity to prevent violence and punish offenders on their lands.

Stay tuned for more updates on my 2020 Spring Road Trip. I promise you there is important and really good stuff happening to give us all a better future.