By Jan Roberts, Founder Cultural Innovations in Action

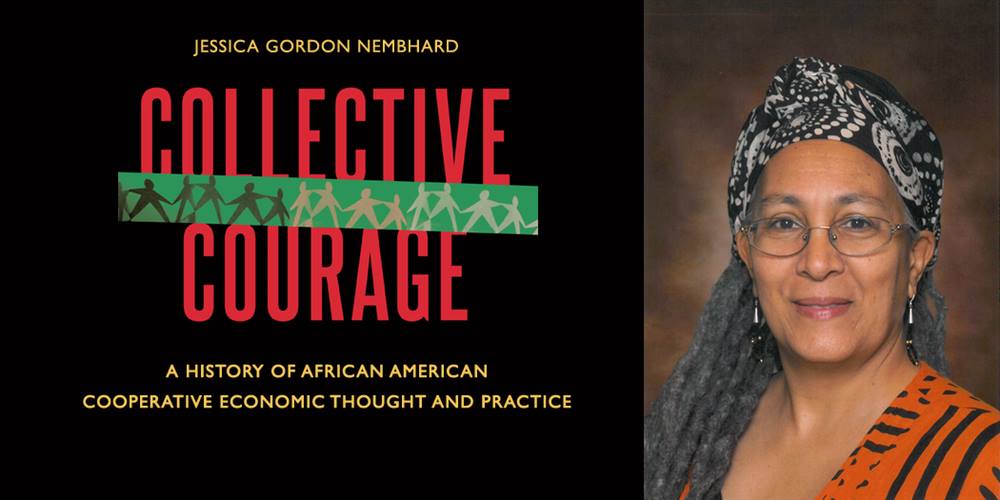

I was so excited to read Jessica Gordon Nembhard’s book: Collective Courage: A History of African American Cooperative Economic Thought and Practice. It is a pathbreaking book. It took Nembhard ten years to research and write it, because the history of cooperatives and the key role of African Americans in them is difficult to find and unravel from the few records and sources that do exist.

Why was I so excited to find this book? Stay with me here. I am a fan of reparations, which happens to be a focus for a documentary I am producing at the end of 2021. AND, one form of reparations besides direct payments by the U.S. government to descendants of the enslaved is community wealth building in Black communities. AND, a very successful approach to wealth building is cooperatives, especially worker owned and farm cooperatives.

For example: Evergreen Worker Owned Cooperatives in Cleveland are three commercial sized cooperatives that have captured the purchasing power of major place-based institutions such as University Hospital, Cleveland Clinic and Case Western University, keeping part of the billions they typically would have spent on vendors for goods and services outside the community within the community. Evergreen offers worker owners good livelihoods, generous benefits, a share in the profits and decision making while donating a percentage to an incubator for cooperatives and towards local community wellbeing. Evergreen is a national model that is being adopted by other cities.

Nembhard points out that “African Americans have a long rich history of cooperative ownership, especially in reaction to market failures and economic racial discrimination. However, it has often been a hidden history and one obstructed by White supremacist.”

Cooperatives seemed to have sprung from the “spirit of revolt, which led to widespread organization for the rescue of fugitive slaves among Negroes themselves, and developed before the war in the North and during and after the war in the South into various cooperative efforts toward economic emancipation and land buying. Gradually these efforts led to cooperative business, building and loan associations and trade unions.” (W.E.B. Du Bois 1907 Economic Co-operation Among Negro Americans. Atlanta: Atlanta University Press) Du Bois also believed that “religious camaraderie was the basis for African American economic cooperation and churches, secret societies and mutual-aid societies among enslaved and free alike created the beginnings of economic cooperation.”

Nembhard writes that “The majority of early African American cooperative economic activity revolved around benevolent societies, beneficial societies, mutual aid societies and more formally and more commonly, mutual insurance companies…They established education, health, social welfare, moral and economic serves for their members. Chief among the activities was care for widows and children, elderly and the poor and provision of burial services…The purpose was to provide people with the basic needs of everyday life—clothing, shelter, and emotional and physical sustenance.”

Here’s a fact that I love!! And it dates all the way back to the 1790s. Who knew?? “By the 1790s, women had established their own mutual aid and beneficial societies. Black women were often in the vanguard in founding and sustaining autonomous organizations designed specifically a to improve social conditions within their respective communities. In creating autonomous institutions to solve the problems caused by inadequate health services, etc. They established day nurseries, orphanages, homes for the aged and infirm, hospitals, cemeteries, night schools and scholarship funds. They pooled meager resources sponsored fund raisers, solicited voluntary contributions and used modest dues that even the poorest women managed to contribute to meet vital social welfare needs. Women’s mutual aid societies proliferated and were sometimes more numerous than all male or men-oriented ones and became influential in Black community throughout the 1800s and into the 1900s.”

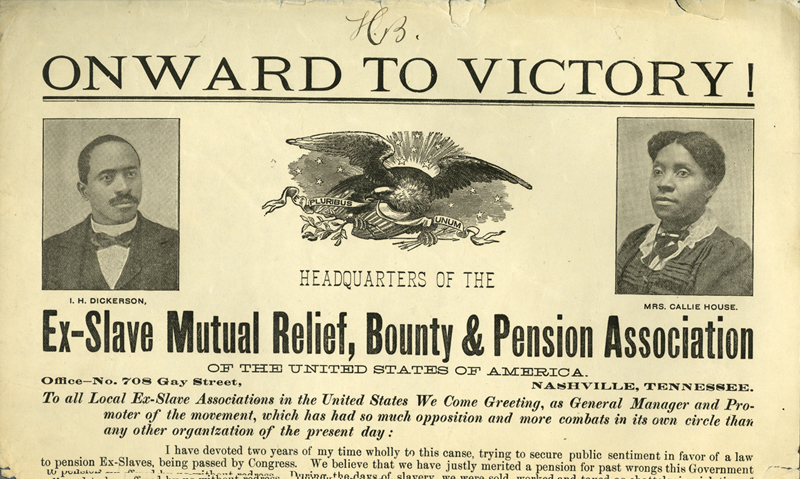

One more exciting fact that I cannot resist. The FIRST fight for reparations for former slaves was the effort of a woman—Callie House, who established the Ex-Slave Mutual Relief, Bounty and Pension Association. “The Association took on what was essentially a poor people’s movement demanding pensions for the formerly enslaved to compensate for years of unpaid labor. It also provided medical and burial assistance. It emphasized self-help and local chapters were required to use part of their dues for sick benefits and burial of members.”

Black women were involved in many efforts to improve the wellbeing of African Americans socially and economically. Nembhard offers a treasure chest of their stories. I just have to mention one more. “Dorothy Height, the president of the National Council of Negro Women suggested they set up a pig bank in Mississippi modeled after the Heifer Project’s international programs. These families cannot live on veggies alone. There must be meat on their tables. The National Council of Negro Women purchased fifty-five pigs and donated them to start the pig bank in Ruleville, MS. Participating families were trained to care for pigs, to establish a cooperative and to work together to improve community nutrition and health. They were assigned a pregnant sow and signed an agreement to not sell the pigs but would donate one piglet from each little to the bank to help more families feed themselves.”

Besides the fact that Collective Courage offers a way forward with one form of reparations—a path blazed by African Americans themselves, it is a powerful tribute to African Americans’ cooperative spirit, courage and organizing power in the face of their unspeakable reality. I urge you to read it.